PROCEDURE GUIDES

DRUG DEPENDANT APPLICATIONS

by Ahmad Kamar Jamaludin,

Senior Sessions Judge, Melaka Court.

ARREST OF SUSPECTED DRUG USER

Police

conduct raids in Discos, Pubs and general nighlife areas in the wee hours of the

morning and take into custody persons suspected to abuse dangerous drugs. Red or

yellowish watery eyes, sluggish and erratic behaviour, long unkempt hair, typical

drug user appearance, the notoriety of the place they are found in and

information they have received all play a role to give rise to suspicion. A

person arrested on suspicion of being a drug dependant will have his urine

sample taken. He will be brought before the Magistrate within 24 hours by the

investigating officer (not below the rank of sergeant). The next course of

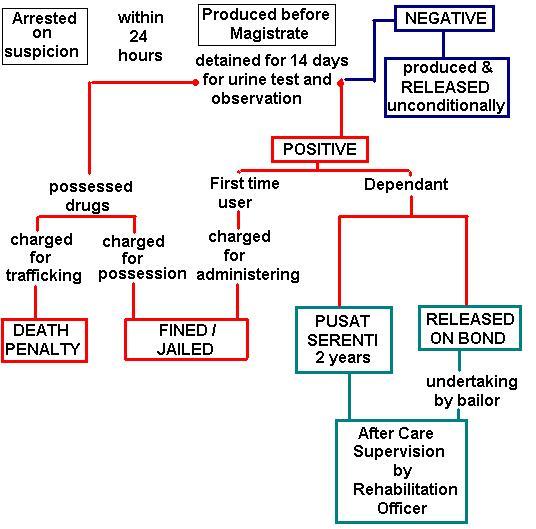

action is best described in this diagram:

INITIAL DETENTION

Under

section 4(1)(a) of the Drug Dependant (Treatment and Rehabilitation) Act 1983 he

can be ordered to be detained up to 14 days and a mention date is given.

He will be

detained in a detoxification centre for observation by a doctor. He can not be

detained in an ordinary lock-up because he is a patient. Tests will be

conducted to see if there are traces of any scheduled drugs in his urine. He

will be observed for symptoms of drug dependant.

TEST RESULTS

If his

test results turn out negative, he will be brought back immediately before the

Magistrate to be released from custody.

If his

results are positive, and the doctor certifies that he is a “drug dependant”.

The doctor will also know if he is a first timer. First timers normally get

high on small amounts. Such small quantity in urine and absence of addicted

symptoms will indicate that he is not an addict. When a user gets immune to

small amounts and needs higher fixes it will show in his urine. In fact drugs

from the opiate group (morphine, heroin are derivatives of opium) will last in

the body system for 4 to 5 days unless the user drank a lot of water to dilute

it. Tests for opium derivative drugs in urine take shorter time (may be 1 – 2 days)

than tests for Cannabis or ganja which take several weeks for the culture to show

results. Hence longer dates for suspected ganja users.

If the

results are positive, the drug rehabilitation officer will prepare a report on

him and make recommendations in his report on how the Court should deal with

him. He will be produced on the mention date given the first time he was

produced.

ON THE MENTION DATE WHEN RESULTS ARE READY

This is

the normal scenario. The suspect appears before the Magistrate. The police officer

tenders the doctor’s report which says that the suspect is found to be a drug

dependant addicted to the drug “heroin” . The interpreter tells that to the

suspect and that he can be relased on a bond or sent for rehabilitation, and whether

he wants legal representation by a lawyer.

If he does, the court may adjourn the hearing for the suspect to hire a

lawyer. If he does not want to hire a lawyer or fails to hire a lawyer, and

admits the doctor’s report, then the Rehabilitation report is tendered by

officer from National Drug Agency (Agensi Dadah Kebangsaan). This officer would

have visited the family of the suspect to investigate the background and

antecedents of the suspect and will write out a report with a recommendation in

the end on how best to deal with him. He wont merely get all the information

from the addict. This report is read out and explained to the addict. Now the

addict is given an opportunity to choose which course of action the Court

should consider and the grounds of which he relies to choose that course.

Normally the addict would say “I am not a hard-core addict, only occassionally

I use drugs, I was spoilt by my friends, I will turn over a new leaf, my family

is here, I have a bailor, give me a chance, I will not take drugs again” etc.

Seldom do addicts choose to go to Pusat Serenti saying they want to get

rehabilitated.

PUSAT SERENTI FOR ADDICTS FOUND TO BE POSITIVE

Under

section 6(1)(a) of the the magistrate may send him for rehabilitation for a

period of 2 years. The Pusat Serenti is not a prison. It is a hospital to treat

drug addicts. Treatments vary according to seriousness of the case.

“Cold-Turkey” or complete cut-off from drugs is the cheapest method used but it

brings about bouts of severely dementing withdrawal symptoms. I believe now the

government is considering “substitution” where some other non-addictive drug is

sustituted to wean them off the habit. There have been cases of completely

rehabilitated addicts released from Pusat Serenti. There have also been cases

of relapse when society discriminated rehabilitated addicts which drove them

back into their old habits. After release from a Pusat an addict may be asked

to be under probation and supervision of the Rehabilitation Officer where the

cured addicts is asked to visit and provide urine sample to the officer who

keeps tab on his further progress. The released person may also be required to

sign a bond and one of the conditions would be not to visit his old co-addicts

or drug hide-outs. It is a arrestable criminal offence not to stick to the

conditions of the bond without excuse, like “I went back to collect my things”.

PROCEDURE GUIDES

BAIL BOND FOR ADDICTS FOUND TO BE POSITIVE

Or under

section 6(1)(b) the Magistrate may release him under a Bond with conditions that someone stands as a

surety (bailor) who undertakes that the dependant rehabilitates himself (see sample conditions) and that he reports periodically to

the rehabilitation officer for a specified period. Most of the time the

Magistrate will follow the rehabilitation officer’s recommendations. When the

Rehabiliation officer visits the family of the addict he would take note of the

family’s commitment in endeavouring to cure the addict on their own, like

sending him for herbal or traditional treatment. There is a family (muslim)

which weaned a lumber-jack addict off the habit by susbstituting alcoholic

stout. During the decision day for the application, the family of the addict can

attend the hearing and can state their undertakings to provide security in the

form of bank book (containing money in the account, of course!). The focus of

pleading with the Magistrate should be on curing the addict and not on the

family’s suffering if he is sent away, because if the addict is concerned about

the family he would not have strayed into becoming an addict in in the first

place .

THE CASE OF FIRST TIME DRUG USER AND NOT A “DEPENDANT”

If the

arrested and found to be a first timer, and not a dependant because he did not

show the symptoms of a dependant, he may be instead charged for the offence of

administering drugs on himself under section 15(1)(a) and fined or jailed.

PROCEDURE GUIDES

POSESSION OF DRUGS

Persons arrested for possessing

drugs in their persons will be charged under differenct law, Dangerous Drugs

Act, 1952. Possession of different types of drugs have different sections in

that law to punish them. He who has in possession more amount than necessary

for his own use will be presumed a “trafficker” and the panalty for trafficking

in drugs in Malaysia is death by hanging.

See the complete drug offences summarised in a schedule.

If a drug addict is also found in possession of unused drugs in his person, he

will be charged and sentenced and ordered to undergo rehabilitation in Pusat

Serenti after his release from prison for the remaining period out of 2 years

if his sentence was less than 2 years.

REPEAT OFFENDER

If he is

repeat offender and found to have breached his earlier Bond, he may be fined or

jailed first and ordered to go for rehabilitation for 6 more months after his

release. His surety may be called up to show cause why the security deposit

should not be forfeited.

GENERAL RULES

The drug

dependant ‘s case is an administrative proceeding. It is not a court trial like

other criminal cases. It will be conducted privately in chambers of the Magistrate

or in open court with unnecessary public excluded. Only the immediate kin of

the drug addict are allowed to watch the proceedings.

The

doctor’s report is taken as conclusive unless the dependant can come up with

proof of technical mistakes in procuring and testing his urine without

contaminating it.

There is no appeal against decision of Magistrate when the drug dependant is ordered to be rehabilitated. There are several judgments which outline the importance of following technical aspects of the Drug Dependant Applications done in Magistrates’ Courts. Similar techinical compliance is stressed in cases of arrest and detention under the Internal Security Act and the Dangerous Drugs (Special Preventive Measures) Act 1985, and the Dangerous Drugs (Forfeiture of Property) Act 1988. Agrieved persons have filed Writ of Certiorari and Writ of Habeas Corpus and got off on technicalities non-conformities:

.

RE ROSHIDI

BIN MOHAMED

[1988] 2

MLJ 193

The detainee

had been detained by an order of the learned magistrate under s 6 of the Drugs

Dependants (Treatment and Rehabilitation) Act 1983. The detainee had been

arrested by the police on suspicion of being a drug dependant and had been

taken to the General Hospital where he was examined by a medical officer. The

learned magistrate subsequently ordered him to be detained under s 6(1)(a) of

the Act. It was contended in this case that the learned magistrate had not

complied with the mandatory provisions of the Act in that she had failed to

make any record on whether she had complied with the various sub-ss of s 6,

namely, sub-ss (1), (3), (4) and (5).

Held: in this

case, in the absence of the record of proceedings kept by the learned

magistrate, it was impossible to hold that the mandatory requirements of the

law had been complied with and therefore the application must be granted and a

writ of habeas corpus issued.

Some even have sued the Magistrate, because of section 29 of the Act.

Mohd

Faizol bin Mohamad v Magistrate, Magistrate’s Court, Kulim & Ors

[1998] 4

MLJ 442

The

applicant was ordered to be detained at the Serenti Rehabilitation Centre by

the magistrate pursuant to s 6(1) of the Drug Dependants (Treatment and

Rehabilitation) Act 1983 (‘the Act’). The applicant applied for the writ of

habeas corpus for his release from the detention centre on the ground that he

was denied the right to make a full and proper representation and that he was

being unlawfully detained. The federal counsel raised a preliminary objection

that the applicant was wrong in procedure in applying for a writ of habeas

corpus to secure his release from the detention. It was argued that an order

under s 6 of the Act, so long as it is proper in form and bears the signature

and seal of the magistrate, could not legally be challenged by way of habeas

corpus but only by way of certiorari.

Held,

overruling the preliminary objection:

The

submission of the federal counsel, if accepted, would be tantamount to this

court taking a step backwards in terms of protecting the liberty of the

subjects of this nation. The efficacy of the writ of habeas corpus would be

seriously impaired and it would be a radical departure from the existing

principles on habeas corpus. Such a proposition would be contrary to art 5 of

the Federal Constitution which confers on a person the right to make an

application for a writ of habeas corpus. In the circumstances, the applicant

would not be proceeding on a wrong footing in applying for a writ of habeas

corpus. The magistrate in issuing the detention order had committed a serious

breach of procedure by denying the potential detainee the right to make a full

and proper representation. The detention order would be of no effect as it was

a defective order and any detention of a person under that order would be

unlawful as it would be contrary to art 5 of the Constitution (see pp 446G–I

and 447A–D).

Since the

Act came into force, there have been cases questioning the mode of challenging

the Magistrate’s Order.

Mohd Raymee bin Ismail v Ketua Komandan, Pusat Serenti Tiang Dua

& Anor

[1998] 7

MLJ 376

This was an

application by way of writ of habeas corpus to quash the order of the

magistrate, ordering that the applicant be admitted to the custody of Pusat

Pemulihan Serenti, Tiang Dua Malacca for two years. The application was made on

grounds that the applicant was not given a copy of the report by the

rehabilitation officer and that the report, although was read, was not

explained to him, thus resulted in the order of the magistrate being not in

compliance with s 6(3) of the Drug Dependants (Treatment and Rehabilitation)

Act 1983 (‘the Act’). Not contesting the allegations of the applicant, the

respondents on the other hand objected to the application itself by saying that

it should be done by way of certiorari and not by writ of habeas corpus. The

fundamental issue to be determined was whether in such an application, a writ

of habeas corpus was the proper procedure to be adopted to quash the earlier

order.

Held, allowing

the application:

(1) Not supplying a copy of the report by

a rehabilitation officer to the applicant, as alleged at a para 5 of the

supporting affidavit and which allegation was not denied by the respondents,

was a clear breach of s 6(3) of the Act. Since the consequence of an order

under s 6 of the Act is penal in character, there must be strict compliance

with the terms of the legislation authorizing the order (see p 383B–C).

(2) Not all orders under s 6 of the Act

involve detention. Where an order does not involve detention, the only course

to quash such an order is an application in certiorari. However, in an order

that involves detention, there is nothing to say that an application in habeas

corpus is not available (see p 384C–D).

(3) To restrict a person by requiring

that he must apply by way of certiorari rather than by habeas corpus would be

contrary to the spirit and intent of art 5(2) of the Federal Constitution which

does not impose a restriction as to the procedure of how a complaint is to be

made. Article 5(2) not merely empowers, but requires a High Court or a judge

thereof, upon receiving a complaint and unless he is satisfied the detention is

lawful, to issue an order for the detenue to be produced before the court and

release him.

While certiorari

is a discretionary power of the High Court, a habeas corpus is as of right

under art 5(2). Where it is not disputed that a copy of the report of the

rehabilitation officer has not been supplied to the applicant, it is abundantly

clear that his detention under s 6 of the Act is unlawful and the court must

order the persons holding him to produce him before the court to be released

(see p 384D–F).

And in

Kamaruzaman

bin Yahaya v Menteri Hal Ehwal Dalam Negeri, Malaysia & Anor and other

applications

[1997] 5

MLJ 256

Held, allowing

the applications for habeas corpus:

(1) In this case, the same format in the

form of Form 2 was used, but without the word ‘kerajaan’ after the designation

‘Pegawai Perubatan’ being mentioned in the Form. Unless the word ‘kerajaan’ is

stated after the designation ‘Pegawai Perubatan’, the doctor could not be

presumed to be a government medical officer under the Act. There was no

evidence to say that the relevant hospital in this case was a government

hospital and the court could not take judicial notice of a fact not

contemplated under s 57 of the Evidence Act 1950. In the absence of the word

‘kerajaan’ in Form 2 or positive proof that the certificate was so signed by a

government medical officer, the certificate so produced could not be said to be

a valid medical certificate receivable by a magistrate of its contents under s

6(5) of the Act (see pp 263F–H and 264D).

(2) Making representations means the

right to protest, which by necessary implication and reading it in the context

of art 5(3) of the Federal Constitution, is a right to challenge whatever is

being brought against him. Therefore, it is imperative that magistrates

acquaint and appreciate the meaning of the word ‘representations’ and the

significance and purpose of making representations before exercising their

powers. Although the magistrates were under no duty to explain the meaning and

significance of making representations to the applicants, in order to be fair

to the applicants, especially so when they were not represented by counsel

during the proceedings and furthermore, the inquiries before the magistrates

were in the nature of a proceedings without a trial, it was incumbent on the

presiding magistrates to explain the meaning of the word ‘representations’ and the

significance and purpose of making representations to the applicants, so that

with the explanations, they would know their rights and consequences of the

proceedings. From the pre-prepared notes taken, it did not appear that the

applicants understood the meaning of the word ‘representasi’ (see pp 264E, I

and 265B–C); Mahmod bin Jaudin v Penguasa Serenti Sungai Besi Selangor &

Ors [1996] 3 AMR 2920 followed.

(3) The object of the Act is to provide

for the treatment and rehabilitation of drug dependants, and by its provisions,

the rehabilitation officer’s report is a very important piece of evidence for

consideration by the magistrates. Although the magistrates are not bound by the

rehabilitation officer’s recommendation, nevertheless it plays an influential

role in his decision whether or not the applicants had to undergo treatment and

rehabilitation. The recommendation becomes all the more important to the

applicants as it can be the basis of their objections in the proceedings. As a

result, the omission of the recommendation in the rehabilitation officer’s

report had rendered the report incomplete and defective as well as prejudiced

the applicant’s right to make representations fairly and properly (see pp 265I

and 266A–B).

(4) Generally, the use of the wrong term

to decide a case is not fatal, so long as there is evidence to support the

order or judgment and that the magistrates have complied strictly with the

mandatory provisions of the Act and the Rules. The word ‘menimbang’ includes

‘meneliti’ but not otherwise. They do not bear the same meaning. Since the law

requires the court to ‘consider’ and not to ‘examine’, the use of the wrong

term at the critical stage of the judgment coupled with the presence of too

many flaws in the cases, was fatal to the validity of the detention orders (see

p 266D–E).

RE HAJI SAZALI

[1992] 2 MLJ 864

The applicant was arrested on suspicion of being a

drug dependant. The magistrate ordered the applicant to be remanded at a drug

rehabilitation cetre for two years to undergo treatment and rehabilitation

under s 6(1)(a) of the Drug Dependants (Treatment and Rehabilitation) Act 1983

(’the Act’). The applicant applied for an order of certiorari to quash the

magistrate’s decision firstly, on the ground that the magistrate had failed to

consider the rehabilitation officer’s report as required under s 6(3) of the

Act and secondly, the magistrate had failed to comply with s 6(4) of the Act

when he did not have regard to the circumstances of the case and the character,

antecedents, age, health, education, employment, family and other circumstances

of the applicant. In answer to the application for certiorari, the magistrate

affirmed two affidavits stating that he had considered the matters specified in

s 6((3) and (4) of the Act.

Held, allowing the application:

(1) The

argument that an order under s 6(1)(a) of the Act was not amenable to judicial

review, was not accepted.

(2) It

was not open nor appropriate for the magistrate to subsequently explain or add

reasons to his decision when his judgment showed that he had not apparently

done so. The magistrate’s affidavits would therefore be disregarded since his

judgment itself formed the focal point of argument.

(3) This,

however, does not mean that under no circumstances can a presiding magistrate

make an affidavit when his decision is the subject matter of judicial review.

In certain situations, the magistrate may be justified and indeed entitled to

affirm an affidavit or even to appear at the hearing when his character or bona

fides is called in question.

(4) In

this case, the magistrate gave no reason for the decision. It was also not

shown that the magistrate had considered the matters specified in s 6(3) and

(4) of the Act. Nor was it stated in the note of proceedings the magistrate was

satisfied that the applicant was required to undergo treatment and

rehabilitation under s 6(1)(a) of the Act.

(5) It

is essential that magistrate give reasons for their decision. It is incumbent

on the magistrate to indicate in his judgment that s 6(3) and (4) of the Act

have not been overlooked. No particular form of words is needed for this

purpose. What is necessary is that the magistrate’s mind should be clearly

revealed that he has considered such matters. The absence of any recording that

such matters had been considered, indicates the possibility that such matters

may not have influenced the mental process of the magistrate in arriving at his

ultimate decision.

(6) Section

24 of the Act does not have the effect of relieving a magistrate from the need

to record anything in coming to a decision. Section 24 of the Act deals with

the jurisdiction of magistrates in relation to areas or localities for

exercising the powers under certain sections of the Act.

He can ask for Criminal Revision if the Magistrate had erred. If he disputed the doctor’s report an enquiry must be held by Magistrate to inquire into the procedural correctness of the arresting officer, the doctor and the lab technician. If the doctor’s report is rejected the drug dependant will go free.

ADVICE

Drug abuse

is a dangerous habit. If you are reading this, and you know of someone close to

you has started on drug abuse, please get him to go vluntarily to a counsellor

and save him from getting deeper into the habit. It destroys the the man, his

family, his future and his soul. Early cure will save him.

PROCEDURE GUIDES